It is July 4, 2025, and many major universities (Alan Blinder, n.d.) in the US are struggling to deal with threats and funding cuts from the Trump administration.

A major impact of funding cuts is the loss of enrollments of promising students due to fewer programs. International students now face an even more uncertain future where they may not be able to enroll at all despite being accepted (Harvard Staff, 2025), their student status may be invalidated without notice (Big Immigration Law Blog, 2025), they are detained without recourse for exercising their rights (Charlotte Alter, 2024), or they are detained and denied entry to the US (Melissa Hanson, 2025).

In addition, funding cuts have resulted in universities having to freeze academic programs or renege on accepted students (BestColleges Staff, 2025), jeopardizing ongoing research programs. Also as a side-effect, promising academics both in the US and abroad are looking towards universities outside of the US (Sequoia Carrillo, 2025).

Let’s have a look at the role these academic institutions are playing in the US’s industrial dominance, and the long-term effects of hampering their progress.

Migrations of Intellectual Capital

Throughout history a number of events have contributed to the present distribution of intellectual capital. As of this writing (July of 2025) the intellectual capital – especially when it comes to information technology and biotech – is heavily concentrated in the east and west coasts of the United States.

Use the interactive timeline below to explore important events in the migration of intellectual capital to and within the United States.

For a more detailed treatement, see The Accumulation and Migration of Intellectual Human Capital in the United States: A Historical Analysis.

The American Enlightenment and Colonial Colleges

When: 17th - Early 19th Century

Where: EuropeBoston MAPhiladelphia PANew Haven CTNewport RICharleston SC

European Enlightenment ideas, particularly from thinkers like John Locke, migrated to the American colonies, influencing a distinct American intellectual identity focused on reason, self-governance, and scientific progress. This intellectual capital was concentrated in East Coast port cities, which served as nexuses for transatlantic trade and communication. The founding of the nine colonial colleges, such as Harvard, Yale, and the College of Philadelphia, solidified these urban centers as the primary hubs of early American intellect, attracting scholars and students and creating an environment for the dissemination of new ideas.

Decline

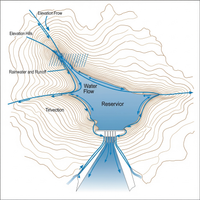

Just as a reservoir relies on its hydro-catchment area to replenish their water supply, intellectual endeavors are similarly dependent on “intellectual catchment areas” —-regions that gather and channel information, ideas, and people.

As a hydro-catchment area’s health dictates the long-term viability of its reservoir; so does the richness and connectivity of an intellectual catchment area directly influence the vitality of intellectual pursuits.

Without these intellectual catchment areas, the wellspring of creativity and innovation for a particular field risks drying up.

Over many decades, particularly starting towards the end of the second world war, the United States has became one of the largest reservoirs of intellectual capital1. While the rise of fascism in Europe drove some precipitation of knowledge into the US in the 1930s and 1940s (L{“a}ssig, Simone, 2017), the intellectual dominance that followed in the decades since the world wars was driven by a positive feedback loop which made the US increasingly attractive to the best minds of the world.

The groundswells of industry established around major universities as well as billions of dollars of research funding from the NSF, NIH, and DARPA created prolific centers of intellectual activity. The Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965 opened the floodgates that were arguably already partially open to international students and skilled labor from all over the world. Out of all this emerged ecosystems of collaboration with regional specializations.

These ecosystems built between industry, government, and academia are collectively the US’s intellectual catchment areas. It took centuries to build what we have now.

What’s more important than what it is, is how the system sustains itself.

And the short answer is that it works because it was working before. We were in a positive feedback loop.

Specifically, the fact that the whole world thinks of the United States as the leader in technology means that all the best minds want to live and work in the United States. The fact that the conditions were favorable for skilled immigrants to study, live, and work in the United States so far means that this dream becomes a reality to millions of people.

It’s not just skilled immigration.

The universities need to continue fostering the thought and collaboration that breeds innovation. Until this year, this positive feedback loop has remained stable. But positive feedback loops can break – especially if one were to violate several of the reasons why the loop exists in the first place.

The ongoing threats against these elite universities at the centers of intellectual catchment areas and the ongoing threats against immigration will undo what took a century to build.

-

The US is not the largest reservoir of intellectual capital. That honor likely goes to China. However in a number of fields, the US is –or was until recently– the most prolific.arrow_upward