The Loss of a Virtuous Culture

Long ago, around 2011, we had an espresso machine in the Google micro kitchen – or MK as we called it – near my desk. There were no baristas at the time, so people made their own. Some folks thought we could use more sophisticated coffee beans than they had in the MK. A designated person would purchase these higher-quality beans using money that everyone collected in a jar in the MK.

This cash jar was not locked. Instead, it was in a conspicuous location, along with a note suggesting that people using the “good” beans should consider dropping some cash there so that people could continue purchasing premium beans.

One day, the cash in the jar went missing.

The response was swift. Donations poured from everywhere in the office, offering to replace the lost cash. Noone speculated on who took the money. Things were back to normal as soon as the incident was reported. The cash jar was re-instated.

The cynic in me wondered why the money didn’t get stolen sooner. But everything worked on the honor system at Google. And we were insistent on keeping it that way.

As far as I know, the money never went missing again, though the cash jar system went away as folks moved around inside the ever-expanding office.

Cash isn’t used as much anymore. However, would a similar system work now? We no longer place as much trust in each other as we did. We don’t even know most of the people we see walking around. But something is going on beyond that. Even if we did know the people, we are now more attuned to insider risk – and justifiably so. As a result, there is more of an air of distrust.

What would be the consequences of a breakdown in mutual trust among employees? In “Upside Decay,” Brian Lui argues that such a breakdown in virtue limits an organization’s ability to benefit from luck.

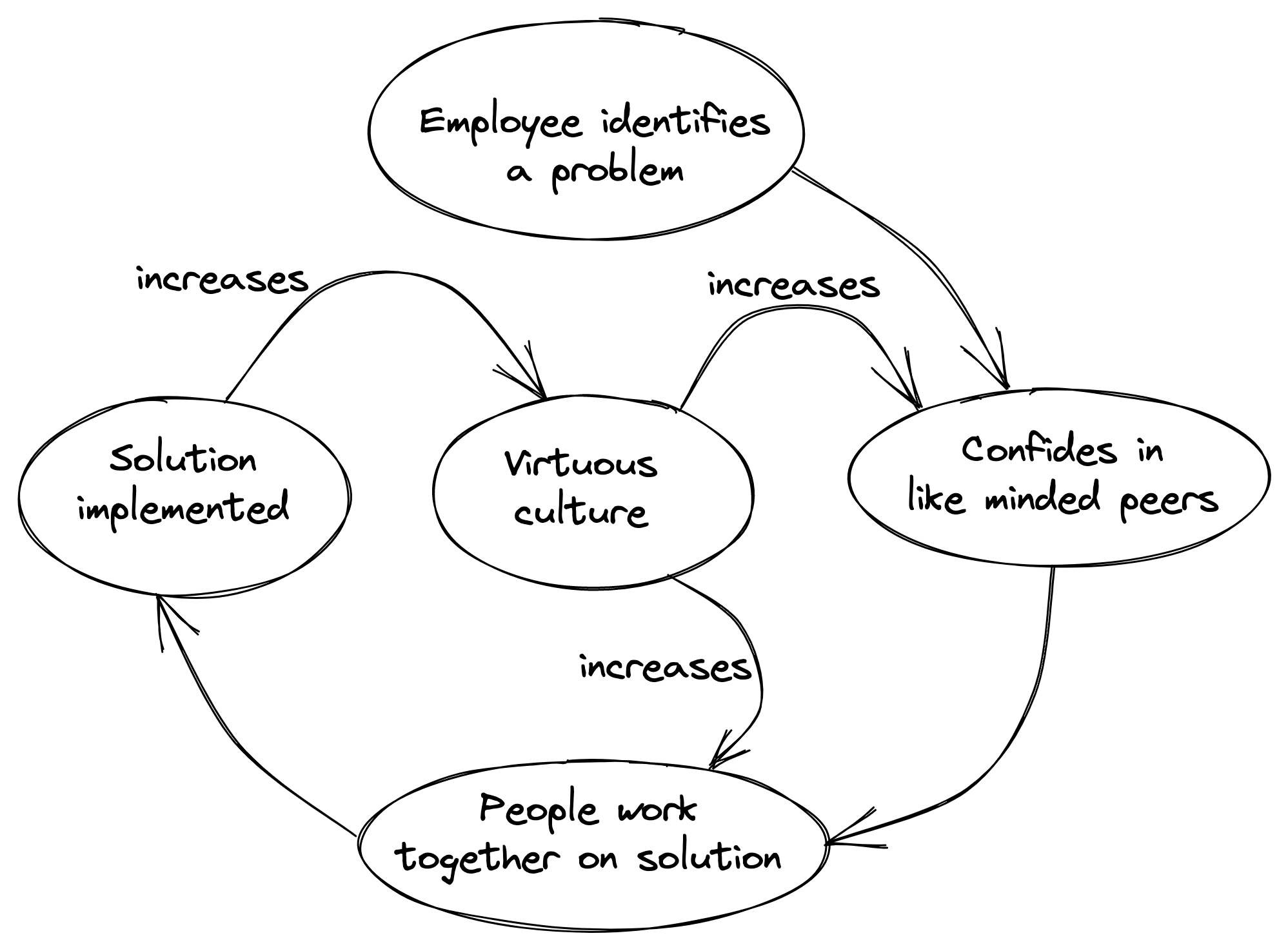

As the diagram indicates, a virtuous culture cultivates collaboration, leading to successful extra-curricular activity beyond their core work, which reinforces the culture. Notably, many of Google’s successful billion-dollar products came about or benefited from unexpected collaborations that were more or less luck. In a culture of mistrust, such associations outside of their core work would never have happened.

Leadership can identify, plan, and account for some contingencies in core work. Non-core work, on the other hand, relies on self organization within the company. That self organization needs trust. Every large project owes its existence to this non-core work.

And that’s not all. Some of this work may well become large products in their own right. Any large tech company will have tons of stories of this happening repeatedly.

The importance of “serendipitous collaboration” isn’t lost on executives. It is the reason behind many pushes for bringing tech workers back to the office.

Last modified: October 28, 2022